| ..

The

Next Level

Accentuated

Stretch and Flexibility for Classical Dance Development and Martial

Arts (Multi-Sport Olympic Development)

Stephen

M. Apatow, Founder, Director of Research and Development, Sports Medicine & Science

Institute

and International

Dancescience Development Program*

[Vitae][Email]

*

Humanitarian Resource Institute, Humanitarian

University Consortium Graduate

Studies Center for Medicine, Veterinary Medicine and Law.

Introduction

The study guide "Classical Ballet Based Biomechanics:

Orthopedics 101" covers the topic of correct postural

alignment and the mechanical ideal. The general rule is that

any movement pattern outside of correct postural alignment, is stressed

and has the capacity to result in injury. This is a reference

point for postural analysis in dance training and sports specific

development programs. In the context of orthopedic diagnostics,

postural analysis is the key to understanding the mechanism of stress

and substantive course of therapeutic action.

Priority

Focus Areas

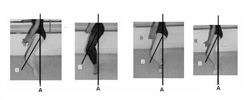

Hip Range of Motion: Turnout

Many

dance and sports injuries, related to the demands placed

on the body and requirement for flexibility in concert with poor

warm-up, can produce Achilles, posterior tibial, and patellar

tendinitis. Repeated jolts, with incorrect postural alignment,

contribute to joint complex deformation and the mechanism of injury.

Rule:

Correct alignment = non-stressed, Incorrect alignment = stressed.

|

In the turned out position, the weight should fall from the

body to the thigh and directly through the knee and

ankle. This distribution of weight can be achieved if the

external rotation of the lower extremities occurs at the hip.

As a rule, external rotation of the foot should only occur to (1) the

mechanical ability to track the knee cap over the center line of

the ankle and foot and (2) the center of gravity (vertical axis) 2

inches behind navel, dropping between the heels (1st, 2nd, 4th, 5th).

|

If a child does not maintain correct knee, ankle, foot

alignment, then the bone and articular level will

stabilize into a permanent developmental deformity (knee, ankle, foot

complex).

Understanding

the Mechanism of Injury

To

achieve increased external rotation of the lower extremity, students

may increase their lumbar lordosis or "screw the knee."

Increasing lordosis decreases the tension on the iliofemoral ligament

allowing increased external rotation of the hip. However, it will

put an excess strain on the lumbar spine, as much a the hyperextension

in gymnastics does. "Screwing the knee" is done by assuming a

demiplie (half knee bend) position, allowing the 180 degree positioning

of the feet to be achieved at the floor, then straightening the knees

without moving the feet. This puts

a great deal of torque on the knees and can produce medial knee strain

and patellar subluxation. "Rolling the foot" can produce

posterior tibial tendonitis and bunions.

Knee

Problems

Medial

knee strain is common in student dancers and presents as pain along the

medial side of the knee with no history of specific injury. Pain

is usually worse after class and gradually decreases if there is

a day or two hiatus between ballet classes. There is no history

of swelling or locking. Physical examination often reveals some

tenderness along the medial aspect of the knee but not specifically

over

the joint line or over the medial collateral ligament. No

effusion

is present. Ligamentous laxity, meniscal signs, and patellar

tenderness

are lacking. Radiographs are not usually required in this

situation.

If one finds tenderness specifically along the distal femoral epiphysis

or along the tibial tubercle or patellar tendon, one is dealing with a

different problem. One can confirm the suspicion of medial knee

strain by asking the child to do a plie. An imaginary plumbline

dropped from the knee should land over the second toe. If the

plumbline

falls medial to the foot during plie, then the medial knee structures

are

seeing increased strain and will gradually respond with pain.

Beware

the child who achieves "knees over feet" by assuming a increased

lordotic position.

In

the ballet class, approximately one half to two thirds of class is

spent at barre exercises, most of which include plies in various

positions. In addition, plies are fundamental to initiating jumps

and landing from them. Hence, if one's plie technique is

incorrect, musculoskeletal problems are quite likely. These

problems can be resolved by explaining the proper technique to the

child. The best way for finding a child's proper position using

external rotation of the hip is to have the child stand with his or her

legs straight and feet together. Instruct the child to move his

or her legs from parallel to a position of comfortable external

rotation, keeping the back straight and head up. The "turnout" achieved

will be a function of the child's femoral neck-shaft angle.

Keeping the knees straight will ensure that the rotation will occur at

the hips. Once in this position, the child can be instructed to

keep his or her feet at this angle, but assume the various ballet

positions. While performing plies in these positions, the knees

should fall directly over the feet. Most good ballet instructors

will accept this variation in positioning of their students and realize

that not all students can achieve a 180 degree angle of their

feet. In addition, good instructors will teach the children to

obtain more external rotation using the short external rotators of the

hip rather then cheating with lordosis of the lumbar spine or twisting

the knee.

Patellar

Tendinitis

Patellar

tendonitis, often a part of the presentation of Osgood-Schlatter

disease, is seen in both the young dancer and gymnast. Patellar

tendonitis is also called "jumper's knee" because it is commonly seen

in athletes who jump often. These athletes have pain in the

patellar

tendon unit, either at the distal pole or the patella, along the

patellar

tendon, or on the tibial tubercle.

On

physical examination, one will find very specific point tenderness at

the site of inflammation. Often swelling will be present in the

infrapatellar bursa. The child also may have pain when extending

the leg against resistance. Usually jumping activities are the

cause.

In addition, Micheli (Micheli, L.J., and Rosegrant, S.: Boston

sports medicine: Helping the young athlete. Phys. Sports med.,

9:105-107,

1981) feels that the "overgrowth" syndrome contributes to the

prevalence of Osgood-Schlatter disease in the 11- to 13-year-old age

group. Although children are assumed to be naturally flexible,

poor flexibility and inadequate warm-up were factors in over half the

injuries seen in Micheli's clinic.

The

treatment for patellar tendonitis is rest. The child may do any

activities that do not aggravate the problem. Generally, forceful

kicks, jumps, and plies must be temporarily avoided. Ice massage

over the tendon area will often decrease the pain as well as the

inflammation. In resistant cases, a jumpers knee brace, a knee

sleeve with a pad over the patellar tendon, will decrease the forces

applied to the tendon by the quadriceps muscle and relieve the

pain. Exercising the quadriceps muscle is to be avoided initially

because it will aggravate the problem. However, when the pain has

decreased, one should initiate stretching and strengthening of the

quadriceps. Symptoms generally resolve in

three to four weeks.

Excerpts

from Sports Medicine Concerns in Dance and Gymnastics

Carol

C. Tetz, M.D. Assistant Professor, Orthopedics, University of

Washington, Seattle, Washington

Pediatric

Clinics of North America, Vol. 29, No. 6, December 1982

Clinics

in Sports Medicine, Vol 2, No. 3, November 1983

Part

II: Accentuated Stretch and Flexibility Exercises to Increase Turnout

Most

dancers and athletes don't know that a lack of turnout or hip range of

motion could be caused by soft tissue restrictions, which can be

addressed with an accentuated stretch and flexibility program.

I

personally began dance training in my early 20's, as an athlete training for

international competition in cycling, skiing and rowing. Dance

training was pursued to optimize balance, economy and leverage

mechanics for skating techniques in cross-country skiing. In

conjunction with my sports specific training, my first 3 years

encompassed intensive modern, jazz and ballet (Lee Lund: Jaime Rogers).

In 1987, I progressed to the study of the Soviet System of ballet

training at the Nutmeg Conservatory for the Arts.

My background in studies in sports medicine, exercise physiology and

biomechanics, helped with the analysis of the physical demands of the

dance training, leading to the development of intensive spine and

extremity flexibility programs. In the context of turnout, by the

time I reached Nutmeg Conservatory, I had more turnout that 95 percent

of the students in the development program.

I had a chance to integrate this work with dancers preparing for international ballet competition,

in an experiment that yielded immediate functional improvement of

flexibility (turnout, shoulder complex, spine, extremity) and technical

performance. Shortly thereafter, a general stretch series was

developed for all levels, pre-ballet through upper level.

Hip

Turnout 101

Programs

that do not operate with

students from a one out of a thousand selection process, need to focus

optimization

of the correctable functional limitations. The conventional

approach

is to throw all children into the same training, without regard for

their

lack of prerequisite flexibility, allowing them to advance (in many

cases

deform) to meet the physical demands.

During

international summer programs, upwards of 90 percent of older students

(14-17 years of age) could not parallel plie, with correct alignment of

the kneecap over the centerline of the

ankle and foot. This was due to articular stabilization of the

ankle/knee complex from poor training. The inability to maintain correct

alignment in the parallel, meant that they were not capable of working

in any turned out position without risk of injury. The majority

of these students work with perfect turnout of the feet in the

technique classes, via complete disregard of the alignment problem by

instructors.

Turnout

specific stretch sequences are

classical ballet specific and a fundamental prerequisite for a warmup

progression.

A stretch series that prepares the student for demands of the classical

ballet

training must be completed for a minimum of 30 minutes before every

classical ballet technique class.

Note: Pilates and Yoga do not accomplish the

joint rage of motion needed for the correct execution of classical

ballet

specific training. Stretches must be classical ballet

alignment

specific.

Postural Alignment of the Shoulder Complex and the Mechanism of Joint

Stress and Injury

Postural

alignment of the shoulder complex is one of the most neglected areas,

second to hip turnout, in classical ballet training.

|

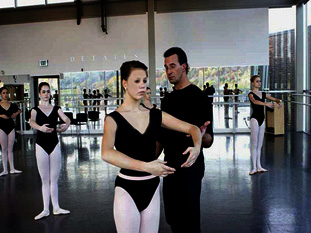

Port de bra demonstrating upper

extremity alignment where (1) the shoulder complex is held back and

down, (2)

head of the humorous stabilized as far behind the clavicular head as

possible, (3) major muscle groups include concurrent contracture of the

pectoral and latissimus muscles to stabilize the shoulder complex and

stercliedomastoid muscle for the cervical spine.

The flat back position (non-winged

scapulas), encompasses optimal connection of the arms to the upper

extremity.

|

Shoulder

Stretch

Range

of motion of the shoulder

complex is crucial for correct alignment of the upper extremity.

Holding

a rigid band, rope or pole, position the hands in a position wide

enough (elbows

rotated up in port de bra position),

then progress to a smooth transition overhead. As the range of

motion

opens, bring the hands closer together. Olympic swimmers possess close

to the mechanical ideal, with hands at shoulder width.

Note: The arms must be held straight, with all movements executed below

a threshold of discomfort.

Mechanism of Injury

The

functional arc of elevation of the shoulder is forward with impingement

occurring predominately against the anterior edge of the acromion and

coracoclavicular ligament. 1 As the head of the humorous

bone shifts anterior to the clavicular head, discomfort may be noted

after the exercise and progress to pain during the exercise resulting

in tenderness over the anterior acromion and greater tuberosity.

The dancer or athlete also has a painful or uncomfortable abduction arc

and positive impingement signs. If the bicipital tendon is

involved,

there will be (1) tenderness over the bicipital grove, (2) positive

straight

arm raising, (3) resistive forward flexion at 80 degrees with the elbow

extended, and (4) positive resisted forearm suppuration.

The

differential diagnosis of impingement syndrome includes (1) acute

traumatic bursitis (caused by a direct blow) (2) primary

acromioclavicular pathology (acute tenderness), or a (3) cervical disc

(neck symptoms and nerve involvement beyond the elbow).

The

complaints related to the shoulder complex and bicipital tendon are

generally

responsive to a restriction in activity accompanied by oral

anti-inflammatory

agents.

Ruptures

of the bicipital tendon have been reported in gymnasts, 2

frequently occurring as a degenerative problem or as a consequence

of sudden unexpected stress applied to the contracted biceps.

Symptomatic bursa formation about the scapula raises the traditional

question of

osteochondroma and need for x-ray films to rule out this rare entity. 3

Thoracic

Outlet Conditions

In

thoracic outlet conditions, the neurologic examination is negative and

radiographs normal with the structure involved difficult or impossible

to identify. It is assumed that the ligamentous support structure

or the joints

between the articular processes have been injured and occasionally,

a symptomatic muscle may be indicated.

Treatment

is tailored to the severity of the problem with analgesic,

anti-inflammatory agents, and possibly a soft collar until there is

full, spasm-free

range of motion. In some patients, a specific neck complaint is

accompanied by intermittent numbness, tingling, heaviness, and fatigue

of an upper extremity, which suggests a thoracic outlet syndrome.

The

outlet syndromes are related to lower elements of the brachial plexus

from

C-7 to T-1. X-ray films may reveal a cervical rib with greater

suspicion

attached to the incomplete or short cervical rib due to the congenital

ligamentous bands coupling coupling the cervical rib to the first rib.

Brachial

Plexus Injury

Upper

extremity weakness as a consequence of participation in contact sports

has been associated with injuries to the upper branch of the brachial

plexus as a probable causative neurologic injury. The is

occasioned by downward force upon the shoulder and deviation of the

head and neck backward or toward the opposite shoulder, suggestive of

traction on the brachial plexus. The distribution of nerves from

the upper trunk includes (1) superscapular (supraspinatus and

infraspinatus muscles), (2) upper and lower subscapular (subscapularus

and teres major), musculocutaneous (coracobrachialis and biceps), (4)

axillary (deltoid and teres minor).

Spontaneous

serratus anterior paralysis is a relatively rare condition. A

common cause is backpacking 4 or a brachial neuritis.

The nerve is the most prominent over the second rib and may be injured

by the undersurface of the scapula with forceful pulling of the

arm. It has also been suggested that injury is due to traction

between the point of proximal fixation, the scalenus medius, and its

point of distal fixation, the superior serratus anterior. 5

Neck

Injury

Barre

described a syndrome with symptoms of headache; retro-orbital pain;

vasomotor disturbance of the face ; recurrent disturbances of vision,

swallowing, and pronation due to alterations of the blood flow within

the

vertebral arteries; and associated disturbance of the periarterial

nerve

plexus. The syndrome is one not frequently expressed in

"whiplash" injuries.

Cervical

spondylosis in the middle and distal thirds of the neck is thought to

be the usual provocative cause of irritation of the vertebral arteries.

Limousin has pointed out that in young individuals, congenital

abnormalities of the posterior arch of the atlas, the arcuate foramen,

man produce the symptoms. 6 The possibility can be tested for by

placing the head in a slightly extended position and firmly gripping

the chin. Firm pressure is then exerted between the thumb and

finger, in a gripping action just below and lateral to the occipital

protuberance, at the level of

the lateral masses of the atlas. Pain may be produced by the

pressure accompanied by conjunctival injection and the shedding of

tears. In some cases there will be a feeling of vague faintness.

Since

many of the patients are young anxious and impressionable, assurance

and conservative therapy are generally all that is necessary.

Many of the symptoms are somewhat confusing and suggest a

supratentorial origin, nevertheless, they should be

investigated. Occasionally, more

particularly with additional complaints of dizziness or staggering,

some disturbance in the vestibular aspect may be established by

nystagmography. 7

References

1.

Neer, C.S., and Welch, R.P.: The shoulder in Sports. Orthop. Clin.

North.

Am., 3:583-591, 1977.

2. Del

Pizzo, W., Norwood, L.A., Jobe, F.W., et al.: Rupture of the biceps

tendon in gymnastics. Am. J. Sports Med., 6:283-285, 1978.

3.

McWilliams, C.A.: Subscapular extosis with advetitious

bursa. J.A.M.A., 63: 1473-1474, 1914.

4.

Ilfeld, F.W., and Holder, H.G.: Winged scapula: case occurring in

soldier from knapsack. J.A.M.A.., 120:448-449, 1942.

5.

Gregg, J.R., Labosky, D., harty, M., et al.: Serratus anterior

paralysis in the young athlete. J. Bone Joint Surg., 61A: 825-832, 1979.

6.

Limousin, C.A.: Foramen arculae and syndrome of Barre-Lieou. Int.

Othop., 4:19-23, 1980.

7.

Toglia, J.U., and Ronis, M.L.: Electronytagmograhpy in

clinical and medical legal uses. trans. Pa. Acad. Ophthalmol.

Otolaryngol.,

22-23-27, 1969.

Selected

Bibliography

Agrippina

Vaganova, Basic Principles of Classical Ballet, Dover, 1969

Alfred

A Knopf, The Classic Ballet, New York, 1984

Clinics

In Sports Medicine, Injuries to Dancers ,Saunders

1983

White-Panjabi,

Clinical Biomechanics of the Spine, J.B. Lippincott, 1978

Rosse-Clawson,

The Musculo-Skeletal System in Health and Disease, Harper & Row,

1970

Stanley

Hoppenfeld, Physical Examination of the Spine and

Extremities, Appleton, 1976

Martial

Arts Specific

JudoSport International

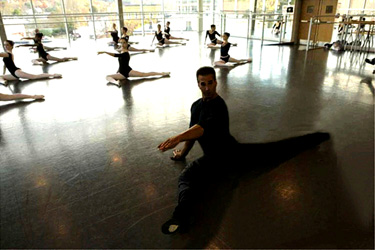

"Kokoro"

is a martial arts training system, developed by Stephen M. Apatow, that

integrate classical

biomechanics into judo, ju_jitsu and mixed martial arts disciplines.

Classical

choreographic training used for Olympic development programs in skating

and gymnastics, provides the foundation for skill development. Martial arts provides a

pathway for teaching classical alignment training for sports and

Olympic development programs.

|

Aspirations

to achieve top level performance requires detailed attention given to

each aspect of the training program. Every day, our diet,

strength, speed, flexibility, postural alignment, mental preparation

and technical training all relate to the factors upon which our bodies

will adapt, to yield our potential performance. -- Stephen M. Apatow

|

|